Time-capsule homes that show America's past

Welcome to early America

From the earliest English settlements to the Wild West, America's living history museums offer incredible opportunities to step back in time and explore the past.

Discover the unique residences built by Native Americans and early colonists, and the innovative ways they adapted to their surroundings while fighting for survival.

Click or scroll to explore these remarkable dwellings...

Colonial Williamsburg, Williamsburg, Virginia

Colonial Williamsburg is a living history museum in the heart of Virginia, the first American colony. The museum recreates 18th-century colonial life as it would have been when Williamsburg served as the capital of Colonial Virginia.

The 301-acre (122ha) site houses hundreds of restored or recreated 18th-century structures across three main thoroughfares. It's the world’s largest living history museum.

Visitors can dine in period taverns, purchase souvenirs in artisan shops and explore dozens of historic landmarks.

Colonial Williamsburg, Williamsburg, Virginia

After falling into post-revolution disrepair, Colonial Williamsburg was restored to its original glory in the early 1900s due, in large part, to generous donations from the world-famous business magnate and philanthropist, John D. Rockefeller.

Significant landmarks were restored, while others which had been destroyed, like the Governor's Palace, were meticulously reconstructed.

Of the roughly 500 buildings in the town, 89 are original, and the overarching result is a bustling merchant square and political capital such as the pre-revolution colonists would have known it.

Colonial Williamsburg, Williamsburg, Virginia

Williamsburg was built as a centre of government around the College of William & Mary. Consequently, it mirrored its Georgian architectural style.

Famed Georgian architect Christopher Wren, creator of St Paul’s Cathedral, also designed the Wren Building at the College of William & Mary, which was the first building to be renovated as part of Rockefeller’s restoration.

Colonial Williamsburg’s buildings range in grandeur from the Governor’s Palace, the magnificent brick residence that was the seat of pre-revolution royal governance, to the humbler one-storey, wood-shingled shops and old cottages.

Colonial Williamsburg, Williamsburg, Virginia

Williamsburg was politically signficant and known for its mercantile industry. Today, historical celebrities such as George and Martha Washington, Thomas Jefferson, James Madison and the Marquis de Lafayette still walk the streets played by incredible actors.

They interact with visitors, while traditional artisans churn out quality goods for purchase.

Merchant Square, the commercial heart of Williamsburg, houses the workshops of blacksmiths, silversmiths, gunsmiths, tailors, cobblers, milliners, coopers, carpenters, printers and of course, wigmakers.

Conner Prairie, Fishers, Indiana

A Smithsonian affiliate, Conner Prairie is a living history museum in central Indiana dedicated to preserving 19th-century midwestern life.

At the heart of the museum lies Prairietown which, though fictional, is based on extensive demographic and geographic research. It's inspired by the early Indiana settlements of the 1830s.

The museum is named for the Conner family, 19th-century north-western pioneers who settled in Indiana at the beginning of the century. They played an infamous role in the removal of the native Lenape people from the territory.

Conner Prairie, Fishers, Indiana

Conner Prairie was established in the 1960s, when the William Conner House and outbuildings were opened to the public as a museum. The William Conner House, one of Indiana’s oldest brick houses, is in the traditional Georgian colonial style.

Using this building as a jumping-off point, the museum curators constructed other early 19th-century farmhouses and buildings on the surrounding land during the 1970s, expanding the museum into what is now Prairietown.

Conner Prairie, Fishers, Indiana

Prairietown recreates agrarian village life circa 1836. An agrarian society is any community whose economy is based on producing and maintaining crops and farmland.

Daily tasks included tending livestock, planting or harvesting crops, preparing food, carding, spinning and dying wool, or working at trades such as blacksmithing or pottery. The community made goods that could not otherwise be obtained.

In a community as small as this, each member was dependent upon the others for the services he or she could offer, and there were certainly no secrets. Prairietown’s costumed interpreters are eager to share pieces of local gossip, or tell stories about the town’s history.

Conner Prairie, Fishers, Indiana

Conner Prairie also includes a traditional Lenape village, where visitors can meet historical interpreters and learn about Native American artistry and trading.

Though tensions were frequently high between native people and settlers, periods of peace could bring mutual prosperity through the exchange of goods and knowledge.

The proximity of Prairietown and the Lenape village is representative of countless early American towns, as settlers vied for ownership of native land and resources and negotiated transient periods of collaboration and conflict.

Frontier Culture Museum, Staunton, Virginia

As the first established colony in America, Virginia attracted settlers from all over the world, all hoping to make their fortunes in the fertile American soil.

The Frontier Culture Museum, which aims to pay tribute to this geographically diverse American ancestry, features original and recreated 18th-century buildings from England, Germany, Ireland, and West Africa.

Visitors can learn about the cultural traditions and contributions of Western pioneers from each place.

Frontier Culture Museum, Staunton, Virginia

Like the early pioneers, many of the museum’s buildings made quite a journey before coming to rest in the Shenandoah Valley.

The museum’s original structures, like this 17th-century German farmhouse, were deconstructed and moved from around the country and even the world to be reassembled piece by piece in their final location.

Frontier Culture Museum, Staunton, Virginia

According to its founder, the museum aims to paint a picture of pioneers both ‘before’ and ‘after their arrival in America.

The buildings representing the native homes of these pioneers show what life would have looked like before their journey to Virginia, while the ‘American’ section of the museum illustrates what it came to look like after they had settled.

This latter section of the museum features a 1700s American settlement, an 1820s American farm, an 1850s American farm, an early American schoolhouse and a 1700s Native American farm.

Frontier Culture Museum, Staunton, Virginia

The 200-acre (81ha) site allows guests to meet costumed interpreters from both the ‘before’ and ‘after’ sections, to learn about their lives and how they came to settle in Virginia.

A West African farmer explains how his daughters were kidnapped by slavers and shipped to America, while an Irish blacksmith’s apprentice dreams of a life free from poverty and hunger across the ocean.

In the ‘American’ section of the museum, tradesmen and artisans describe how their techniques have evolved from their native training to incorporate the new materials available to them in Virginia.

Genesee Country Village and Museum, Mumford, New York

The largest living history museum in New York State and the third largest in the US, the Genesee Country Village Museum is a recreated 19th-century village which comprises 68 historic buildings across 600 acres (243ha).

The museum’s original structures span a century’s worth of history, from the scattered Genesee Valley pioneer settlements of 1795-1830, then the evolution of a more condensed town centre between 1830 and 1870, to the more industrialised post-war ‘Gas Light District’ of 1860-1900.

Genesee Country Village and Museum, Mumford, New York

The museum features an impressive collection of original buildings, all sourced from the across State of New York and relocated to the Genesee Valley in Mumford, New York.

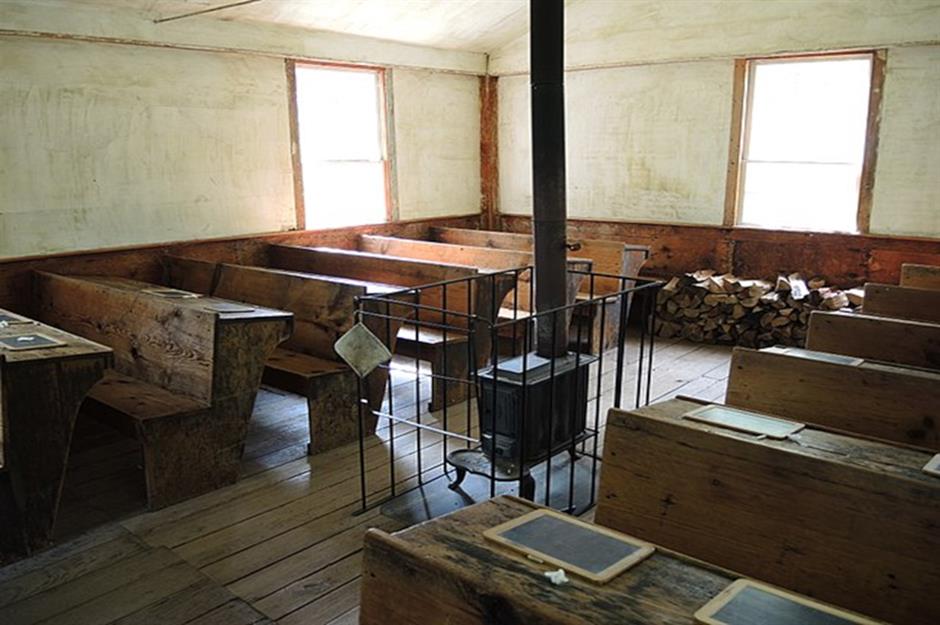

The pioneer settlement section of the village features rustic, wood-shingled buildings constructed during the early to mid-1800s, including this original one-room schoolhouse dating back to 1822.

Here, children ranging in age from three to 15 would attend class in the winter and summer only, as they would be needed at home to help on the farms during the spring and fall.

Genesee Country Village and Museum, Mumford, New York

The Center Village illustrates the mid-19th-century shift from a farm to a commerce-based economy, and is home to the museum’s tradesmen and artisans.

Live demonstrations of contemporary techniques are performed by the local shoemaker, dressmaker, cooper, potter, gunsmith, wheelwright, printer, lawyer and of course, publican.

The Center Village also showcases some beautiful mid-century, Greek-Revival mansions. These were the homes of some of New York’s wealthier entrepreneurs who made their fortunes in banking or the mill industry.

Genesee Country Village and Museum, Mumford, New York

Culture and activity flourish in the most modern part of the museum, the bustling ‘Gas Light District’.

Here, visitors can explore the Davis Opera House (pictured), which served as a general store on the first floor, and on the second as an elegant lecture theatre and music hall. Travelling performers, musicians and even circus acts would entertain locals.

This section of the village also houses the museum’s Silver Base Ball Park, where guests can witness 19th-century base ball (as it was once spelled) games all summer long.

Greenfield Village, Dearborn, Michigan

Greenfield Village is the living history branch of The Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation, the largest indoor-outdoor museum complex in the United States, founded by Ford himself.

The 80-acre (32ha) living history museum was the first of its kind in the country, and is divided into seven ‘historic districts’; sections dedicated to immersing guests in a specific element of 19th-century life.

Four of the districts are dedicated to representing more traditional features of early American village life, while the final three cover scientific innovation.

Greenfield Village, Dearborn, Michigan

Guests begin in Greenfield Village, exploring the sections dedicated to more traditional daily life.

These include ‘Working Farms’, where visitors can explore four different fully operational 19th-century farms; ‘Liberty Craftworks’, where skilled artisans demonstrate authentic techniques; ‘Main Street’, the bustling centre of contemporary commerce and entrepreneurship, and ‘Porches & Parlours’, a series of original 19th-century houses and farmhouses collected from across the United States.

This particular parlour is ready for a 19th-century games night, complete with chess board, playing cards and an Edison's electric lamp.

Greenfield Village, Dearborn, Michigan

An architectural highlight of the village, though it might seem slightly incongruous with its surroundings, is this 1619 Cotswold Cottage, imported from England.

Over several visits to England in the 1920s, Henry Ford fell in love with the quaint and characteristic Cotswolds architecture.

By 1929, so great was his love for these buildings that he decided to purchase, deconstruct and move a Cotswolds cottage all the way to his home in Greenfield, Michigan, where it was reassembled and still stands to this day.

Greenfield Village, Dearborn, Michigan

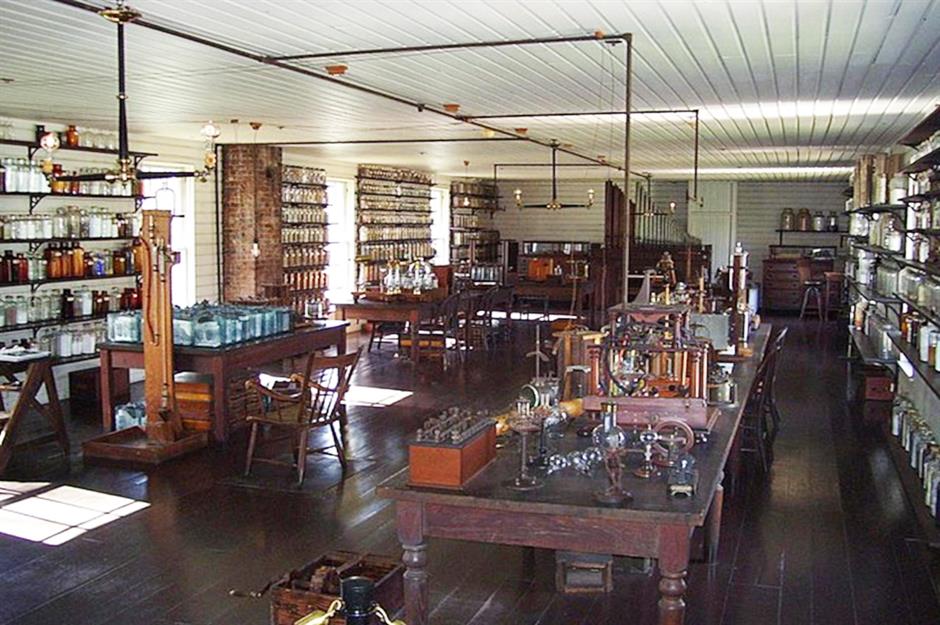

The scientific section of the museum includes ‘Henry Ford’s Model T District’, where guests can trace the life and work of Henry Ford right up to his creation of the Model T, which they can then take for a spin.

There's also ‘Railroad Junction’, where visitors can climb on board a 19th-century steam engine and explore an original 1884 ‘roundhouse’ where trains were repaired and maintained.

Finally, ‘Edison at Work’ provides visitors with the opportunity to set foot in the original R&D (research and development) labs where Edison invented the lightbulb.

Plimoth Patuxet Museums, Plymouth, Massachusetts

Plimoth Patuxet is a recreation of the original Plimoth Colony, a 17th-century Massachusetts settlement established by English colonists who later came to be known as the Pilgrims.

The living history museum comprises a traditional English village, as well as Historic Patuxet, home of the indigenous Wampanoag people.

Guests can stroll down to the harbour and board the Mayflower II, a full-scale reproduction of the ship that brought the English colonists to Massachusetts in 1620.

Plimoth Patuxet Museums, Plymouth, Massachusetts

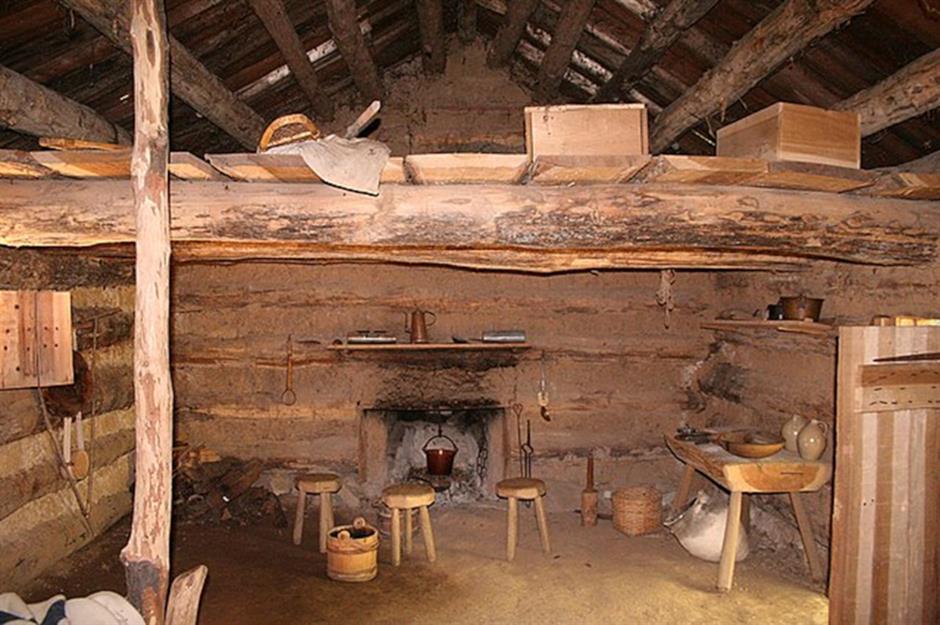

The English village features a collection of reconstructed 17th-century timber-framed houses, each outfitted with reproduction furniture, household items and articles of clothing. Most of these structures consist of only one room and the barest of essentials.

The village is set in the year 1627, when the settlers were desperately fighting for survival in the harsh New England climate.

In the surrounding gardens and fields, third-person costumed interpreters pound corn, pull weeds, or even engage in a ‘muster drill’ led by Captain Myles Standish, commander of the Plymouth Colony Militia.

Plimoth Patuxet Museums, Plymouth, Massachusetts

Before the colonists arrived in Massachusetts, the local Wampanoag people numbered between 50,000 and 100,000 across 67 different villages. Historic Patuxet is a recreation of a traditional Wampanoag village, consisting of a cooking area, fields of crops and several wetus, or houses.

Each wetu is lined with fur-laden benches where the villagers would gather around a fire for storytelling and song to pass the long winter nights and ward off the cold.

Plimoth Patuxet Museums, Plymouth, Massachusetts

Elsewhere in the village, interpreters discuss what life would have been like for the Wampanoag in the 17th century.

Visitors may be invited to play a traditional game made from animal bones, to sample a seasonal dish in the cooking area, to help in the garden planting squash, beans, and corn, or even to help work on a mishoon (a traditional dug-out canoe).

The interpreters, many of whom dress in traditional Wampanoag attire, explain how many of the rich cultural traditions on display in the village are still in practice today

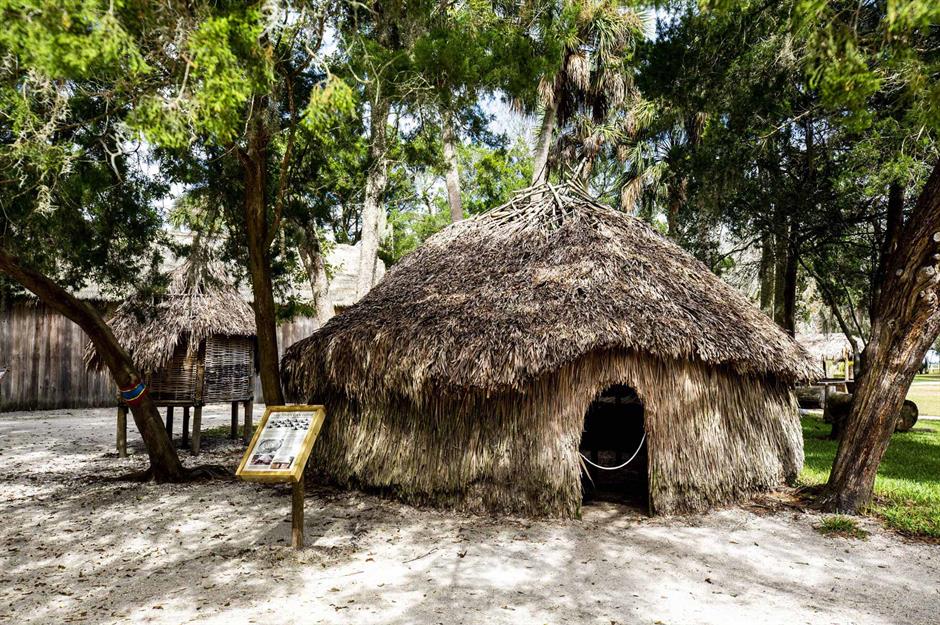

Seloy village, St. Augustine, Florida

First sighted in 1513 by the Spanish explorer and conquistador Juan Ponce de Leon, and settled in 1565 by Pedro Menendez de Aviles, St. Augustine was America’s first European colony.

Of course, like so many American colonies, the land had previously been occupied by the indigenous Timucua people, but the Spanish settlers were soon so numerous that the colony expanded, making it the first successful European settlement in the United States.

Today, the site is a historical reservation known as Ponce de Leon’s Fountain of Youth Archaeological Park, and this intriguing name has an origin story...

Seloy village, St. Augustine, Florida

When Ponce de Leon sailed for the Americas, his intention was to hunt for gold and other precious goods to bring back to Spain. However, upon hearing the Taino (an indigenous local tribe) legend about a spring said to exist on the isle of Bimini which would provide eternal life and youth to anyone who bathed in its waters, Ponce de Leon began his quest for the Fountain of Youth.

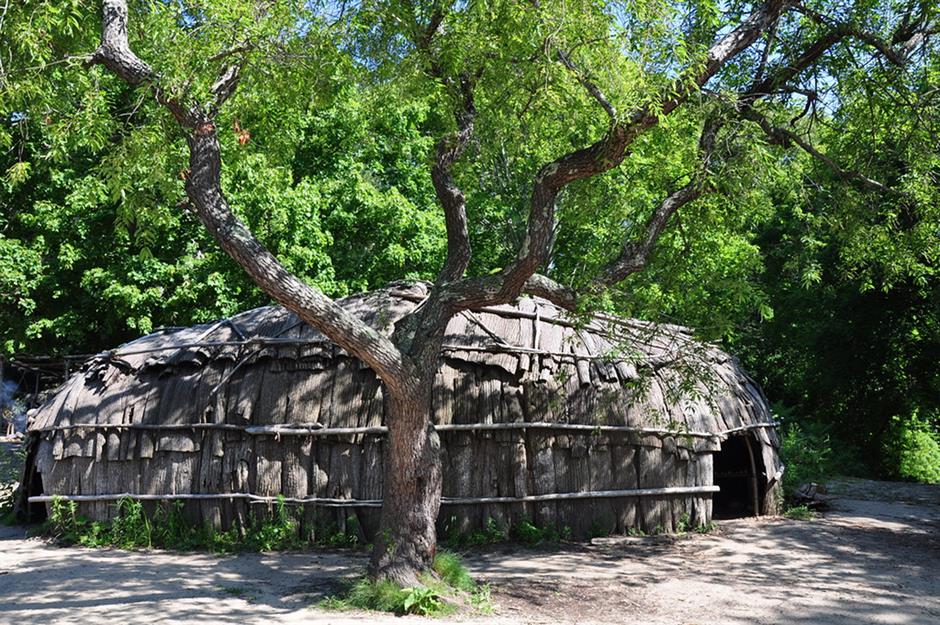

Today you can see a recreated Seloy village (pictured), the original village of the Timucua people driven off the land by Spanish settlers. The structures include a historically informed anoti, or large family house, as well as a nihi paha, or meeting house.

None of the original architecture from the early Spanish settlement survives, but close to the Ponce de Leon park lies more historical homes...

The Oldest House, St. Augustine, Florida

In St. Augustine, the town nearby the Fountain of Youth, you'll find the 'Oldest House'. A National Historic Landmark dating from the early 1700s, its walls are made of coquina, a rare sedimentary rock that was quarried locally.

Also known as The González–Álvarez House after two of its owners, the two-story structure is covered by a hip roof (a roof that slopes downward from all four sides, meeting at a ridge at the top) finished with wooden shingles.

It has an open covered loggia on the east side to allow winds to cool the structure, while the thick walls provide insulation from hot weather. The interior floors are made of tabby concrete, made by burning oyster shells to create lime, then mixing that with water, sand and ash.

The Oldest House, St. Augustine, Florida

The building was altered during different periods of colonial administration. After the González family, who lived in the home from around 1723, left for Cuba and the British took over Florida, the house was purchased by Englishman Major Joseph Peavett in 1744.

He added a wood-frame second storey and put in glass windows. This bedroom is how it might have looked when Peavett lived here.

Third owner Geronimo Alvarez added a two-storey wing built of coquina to the house before it was taken over by the St. Augustine Historical Society in 1918. The society continues to take care of the home and welcomes visitors.

Old Sturbridge Village, Sturbridge, Massachusetts

Old Sturbridge Village is the largest living history museum in New England, recreating rural life from the 1790s through the 1830s.

The entire property consists of 200 acres (81ha) with 59 buildings, both informed reconstructions and original structures collected from across New England.

The village is divided into three sections, with the ‘Center Village’ at its heart. This section consists of civic buildings including a law office, printing office, meetinghouse and bank, all centred around the town green.

Old Sturbridge Village, Sturbridge, Massachusetts

‘The Countryside’ section consists of a collection of homes and farmhouses, as well as a fully operational farm complete with livestock, orchards and various barns and outbuildings.

Sturbridge’s economy once thrived off this land, and the calendar year was structured around the various chores associated with a working farm: sowing seeds, shearing sheep, picking apples and harvesting crops.

Elsewhere in this section of town, the potter, cooper and blacksmith forge the tools necessary to keep the farms in good working order.

Old Sturbridge Village, Sturbridge, Massachusetts

The final sector, the ‘Mill Neighbourhood’, features three different, fully operational water-powered mills: a gristmill, a sawmill and a carding mill. Of the three mills, the carding mill is the only original structure, with both the building and its machinery dating to 1840.

To get a real taste (almost literally) of what life was like for the Sturbridge villagers, you can watch kitchen demonstrations like the one pictured. Costumed interpreters show you how recipes were developed using local produce, then made with original techniques.

Old Sturbridge Village, Sturbridge, Massachusetts

Though Sturbridge was largely self-sustaining in its industries, it was nevertheless a centre of international commerce. It imported cotton textiles from England, France and India, silks from China and Italy and dyestuffs from the West Indies and South America.

These and other luxury goods (both original artifacts and recreations) can be found for sale in the Asa Knight store. They're also on display in the richly appointed Salem Towne House (seen here), an impressively large Federal Style home once owned by a wealthy businessman and justice of the peace.

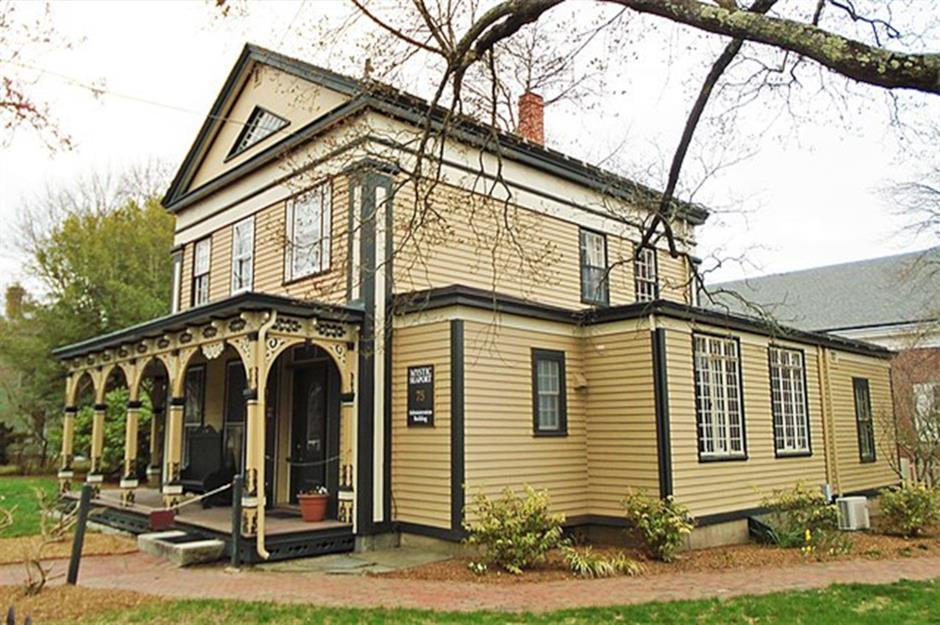

Mystic Seaport, Mystic, Connecticut

Mystic Seaport is a recreation of a once-bustling 19th-century sea-faring village, and part of the larger Mystic Seaport Museum. The buildings are all original structures, transported to the seaport from around New England.

Most of the buildings house trades related to the village’s maritime past. Visitors can explore an historic sail loft, rigging loft, ship carver, ship chandlery and a shop selling nautical instruments.

The museum also houses a collection of historic vessels moored along its wharf, including the world’s last surviving wooden whaleship, the Charles W. Morgan.

Mystic Seaport, Mystic, Connecticut

The seaport village was once a small family business. In 1837, the three Greenman brothers, all trained shipbuilders, bought a piece of land along the Mystic River estuary which they planned to turn into a shipyard.

However, with the success and expansion of the shipyard in the 1840s, the area grew into an industrial ship-manufacturing village known as Greenmanville.

As the local industry expanded, many homes, rental properties and boarding houses were constructed in the area, most of which are still standing and are now a part of the museum.

Mystic Seaport, Mystic, Connecticut

Perhaps the most impressive of these historic buildings is the George Greenman House (pictured), built in 1839 for George Greenman. He was the eldest of the Greenman brothers, and he lived here with his wife Abigail.

He allowed both his younger brothers to live with them until they built their own homes (also included in the museum) in 1841 and 1842 respectively.

The house was designed in the Greek Revival style popular at the time, though the intricate decorations visible today were added later, in the 1870s.

Mystic Seaport, Mystic, Connecticut

Not all of the buildings owned by the museum are open to the public, but visitors can explore inside several of its more historic sites, such as the Mystic Bank established in 1833 and Charles Mallory Sailmakers (pictured).

Mallory came to Mystic in 1816 from London and prospered as whaling and shipbuilding grew in the village. By the 1860s he was one of the state’s most prosperous ship owners.

His sail loft was originally downriver from the Greenman shipyard where the Museum now stands, but it was brought here by barge in 1951.

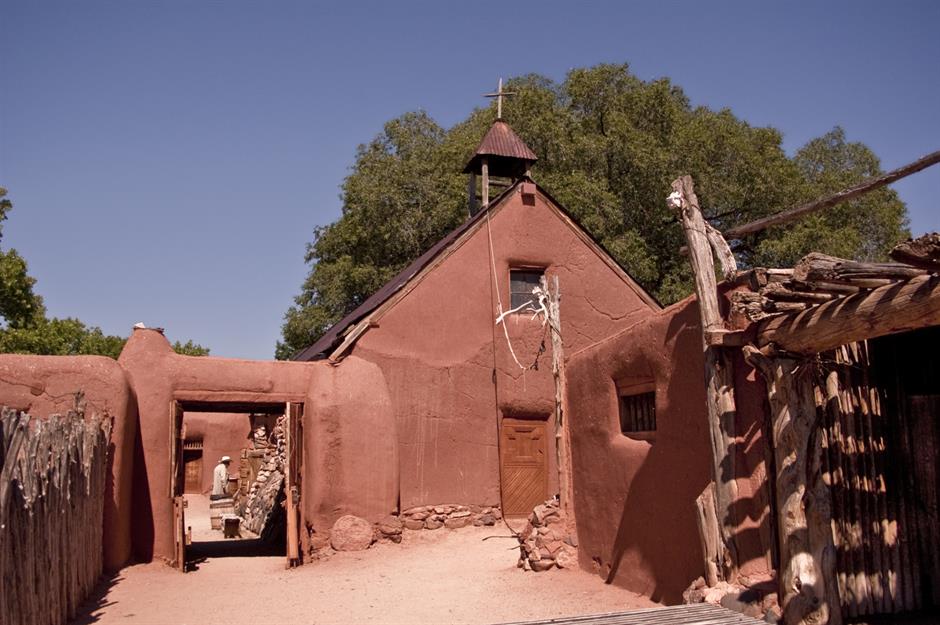

El Rancho de Las Golondrinas, Santa Fe, New Mexico

El Rancho de Las Golondrinas, or ‘the ranch of the swallows’, is a living history museum dating to the early 1700s.

Sitting on the Camino Real, the Royal Road connecting Mexico City and Santa Fe, this historic rancho was once a popular stopping place for caravans en route to the big city, as well as a trading post for goods.

Today, this 200-acre (81ha) site strives to preserve this heritage and culture, offering visitors the unique opportunity to experience life in 18th and 19th-century agrarian New Mexico.

El Rancho de Las Golondrinas, Santa Fe, New Mexico

Once a bustling trading post, the museum features 47 different sites, most of them dedicated to the practice of a specific trade or craft.

Artisans demonstrate traditional techniques including hide tanning, carpentry, wool dying, blacksmithery, or the making of wine among many others.

Visitors can also explore traditional century homes, speak with costumed interpreters and learn about the daily chores and activities of the farmers and traders who inhabited the ranch hundreds of years ago.

El Rancho de Las Golondrinas, Santa Fe, New Mexico

The museum was established in 1972 by Leonora Curtain and her husband, Yrjö Alfred (Y.A.) Paloheimo.

During the Great Depression, Curtain had previously founded Santa Fe’s Native Market, a venue for local artisans to sell their work in an effort to re-establish and preserve traditional techniques of Santa Fe artistry. Curtain demonstrated the same historical enthusiasm in reviving the old ranch site, originally purchased by her mother in 1932.

She tirelessly restored original buildings, imported others from across New Mexico, and erected historically informed replicas. The interiors are as detailed as possible as this kitchen shows.

El Rancho de Las Golondrinas, Santa Fe, New Mexico

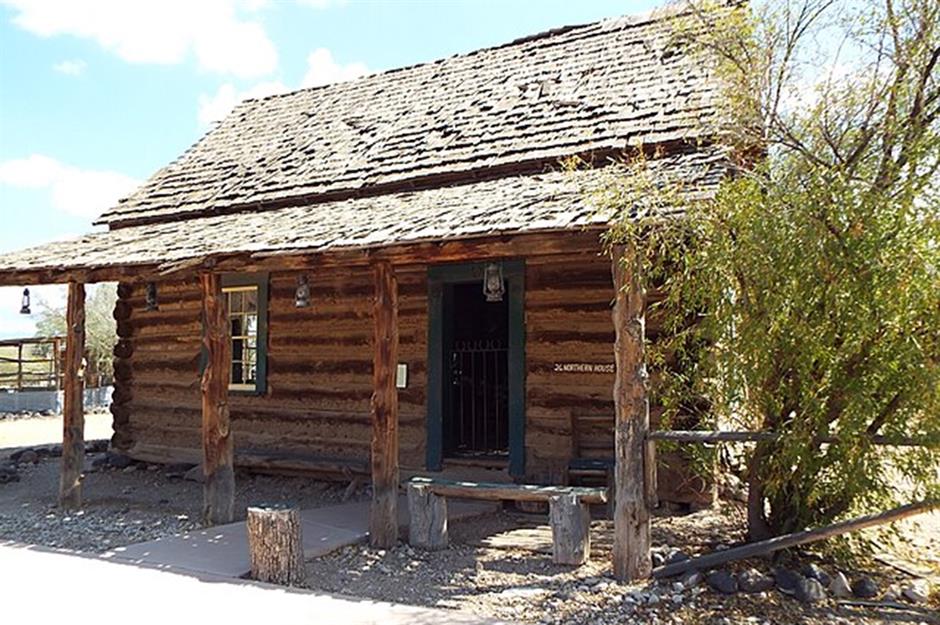

The buildings on display at El Rancho are representative of the range of architectural structures common in New Mexico in the 19th century.

They reflect the cultural influence of both the native Pueblo People, and the Spanish settlers who arrived in the late 17th century. The majority of the buildings are made of adobe plastered with mud, giving them the characteristic soft red colour.

However, some of the more recent buildings constructed towards the end of the 19th century, such as the mill and schoolhouse, are more reminiscent of Western log cabins (pictured).

Jamestown Settlement, Williamsburg, Virginia

The Jamestown Settlement and American Revolution Museum at Yorktown allows visitors to step back in time to the 17th century, where English colonists settled in Virginia in 1607.

Here, they established the first permanent English settlement in North America, ousting the local Powhattan natives and establishing a small agrarian colony dependent largely on the production of tobacco.

Jamestown Settlement, Williamsburg, Virginia

Today, the museum includes many recreations of the original settlement, including colonial homes, the colonist’s fort, one of the three ships that sailed from England in 1606 and several Powhatan homes in a Paspahegh town.

Most of the colonist’s houses, like those pictured here, were made using the 'mud and stud' architectural style, featuring wooden frames, daub walls and a thatched roof.

Jamestown Settlement, Williamsburg, Virginia

The colonial fort, on the other hand, needed a sturdier structure, and was built using a cobblestone foundation laid in clay, a timber frame and lath and plaster walls.

Inside these recreated homes visitors can take a look at the few possessions early settlers might have brought with them from England, essential items such as wooden bedframes, pottery, rudimentary dishes and a chest for clothes storage.

Jamestown Settlement, Williamsburg, Virginia

Over in the Powhatan village, meanwhile, visitors can step inside a traditional yi-hakan, as it was known in the Algonquin language, which consist of long bent sapling poles covered over either with woven reed matting or shaped bark.

The construction of these homes was labour intensive and time consuming and was often completed by women.

With only one door and no windows, they were often dark and smoky inside.

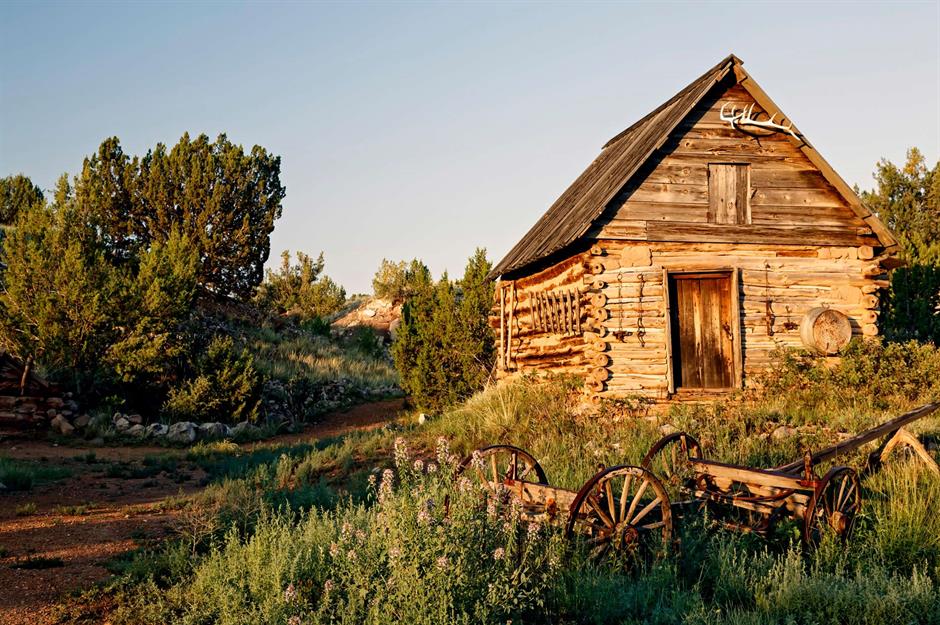

The Pioneer Living History Museum, Phoenix, Arizona

For anyone with a penchant for the Wild West, the Pioneer Living History Museum in Phoenix, Arizona provides an ideal opportunity to explore this unique chapter of American history.

The expansive 90-acre (36ha) open air museum sits nestled at the base of Northern Phoenix’s foothills, and boasts 20 19th century buildings assembled together to create the ‘Pioneer Village.’

A highlight of the village is Ashurst Cabin, the boyhood home of Arizona’s first senator, pictured here.

The Pioneer Living History Museum, Phoenix, Arizona

This collection of homes, shops and community gathering places provides a holistic portrait of a Wild West settlement, populated by a slew of costumed interpreters ready to answer visitor questions.

One of the village highlights is this original log cabin, built using the ‘saddle rider’ notching technique, which was moved 25 miles (40km) from its original location in Newman Canyon.

The house is estimated to date to 1885, belonging to early pioneer Jeff D. Newman.

The Pioneer Living History Museum, Phoenix, Arizona

Guests can also step inside the 'teacherage', another original building which was once the designated residence of a local community’s teacher, a unique concept for its time.

While parsonages had long been used to attract ministers to small, rural communities, dedicated lodging for teachers was very rare for the 19th century.

However, this cosy nest with its simple but charming furnishings may well have been an enticement for a traveling teacher looking for a position out west.

The Pioneer Living History Museum, Phoenix, Arizona

Slightly more modern-looking, Merrit Farm, pictured here, is another of the museum’s original properties, this one dating to 1910. The home was luxurious for the time, consisting of three rooms and a large pantry, later converted to a bathroom, an unheard-of luxury!

The kitchen is housed in a separate structure meant to keep the additional heat away from the main house given the intense Arizona climate.

Loved this? Now discover more incredible historic homes

Comments

Be the first to comment

Do you want to comment on this article? You need to be signed in for this feature