Discover 1940s British home life in stunning vintage photos

Travel back in time to the 1940s

After the glitz and glamour of the 1920s and 30s, the party came to a screeching halt in 1939 as the world went to war once again. We take a look at the impact this important decade had on everyday life, exploring the architecture, décor and habits of a 1940s English home both during and after the Second World War.

Read on to discover life on the home front and how people 'kept calm and carried on'. To enjoy these pictures on a desktop computer FULL SCREEN, click on the icon at the top right of the image...

The world at war

The outbreak of the Second World War brought a drastic changes to daily life, much like the economic crash a decade earlier. On 1 September 1939, Germany invaded Poland, prompting France and Great Britain to declare war two days later.

The conflict rapidly expanded to involve major powers like Russia, China, Japan, Italy and eventually the United States, leading to the deaths of over 60 million people worldwide and widespread destruction.

An international conflict

The US entered the war in December 1941 after Japan’s surprise attack on Pearl Harbor, which claimed over 2,400 lives. By 1945, the Allied Forces (Great Britain, America, Russia and China) emerged victorious. The war’s impact reshaped societies globally, altering everyday life, from clothing and food to overall living conditions.

In England, a genuine community spirit developed and often transcended class and other barriers as people 'battened down the hatches' to protect their homes and lives.

War on the home front

While the war effort was, of course, focused on the frontlines, it dramatically altered the lives of those left behind as well. With the majority of men of working age engaged in combat, women in Britain rolled up their sleeves and joined the workforce in droves to fill in the gaps left behind by husbands, fathers and sons.

Home lives were simplified, family units condensed and many people moved away from big cities, where possible.

The Home Guard

War found its way into British homes in different ways. Many men who didn’t or couldn’t enlist, in most cases due to age, joined the Home Guard or Home Forces, volunteer civilian forces designed to obstruct the enemy on the home front should they invade.

Many boys below the age of 18, like the young man pictured here getting into uniform in his childhood bedroom, chose to enlist in the Home Guard, quite literally bringing the army into the British home.

Rationing and reduction

With supply chains cut off all over the world, the 1940s saw a dramatic reduction in consumption across the board from food and clothes to home goods.

Plus, the majority of factories were repurposed to aid the war effort by producing uniforms, weaponry and other equipment, putting a halt on the production of whatever goods they had previously produced and reducing the number of consumer items available.

Back to basics

With food in such short supply, families queued for hours to collect ration books. These were forms of documentation which outlined the holder’s entitlement to the various goods in short supply due to import reductions.

Rationing forced families to limit ‘luxury’ items such as coffee, sugar, butter, alcohol and certain meats.

Pre-war building boom

During the interwar period (1918 to 1939), semi-detached homes like these were built en masse as part of urban expansion in the UK. Most new homes were built on cheap land on the outskirts of cities and it was a great time for social housing with around 214,000 council properties built by 1939.

These homes were often built in estates of cul-de-sacs and characterised by low-hipped rooflines, curved bay windows and elements of the Arts and Crafts movement, such as pebble-dashed walls, hanging tiles and recessed porches. Tudor-style houses, with their telltale half-timbers, were also popular and the number of private flats surged, with an estimated 56,000 built in London during the decade.

Construction and architecture

The war had an impact on homebuilding and architecture. The high industrial demands on steel and other construction materials during wartime led to new developments in products such as aluminium and synthetics.

Simple, efficient and effective, modernist-style homes dominated the construction market during the war years.

Kitchens in the 1940s

A 1940s kitchen was compact, practical and designed for efficiency. Built-in cabinets were rare; instead, freestanding cupboards and tables were used, with wall-mounted shelving or big pieces such as dressers or sideboards added for extra storage. Colour schemes often featured muted pastels, with floral or checkered patterns on walls and curtains in pinks, pale blues, soft greens and cheery yellows.

With wartime rationing in full effect, kitchens were geared for frugal cooking, preserving food through canning, pickling and preserving, and making the most of limited supplies. They also served as multi-purpose spaces for housework like laundry and sewing, making them the hub of daily home life.

Old and new technologies

1940s kitchens also frequently featured a hodgepodge of appliances, depending on the wealth and location of the household. A new Frigidaire refrigerator might be seen next to an antiquated Chambers stove, for example.

Essentials included a gas or coal stove and an icebox or basic refrigerator, while electric gadgets were minimal and most things were done by hand. Meanwhile, newly developed materials were on full display, with linoleum floors, enamel tabletops and chrome fixtures and fittings.

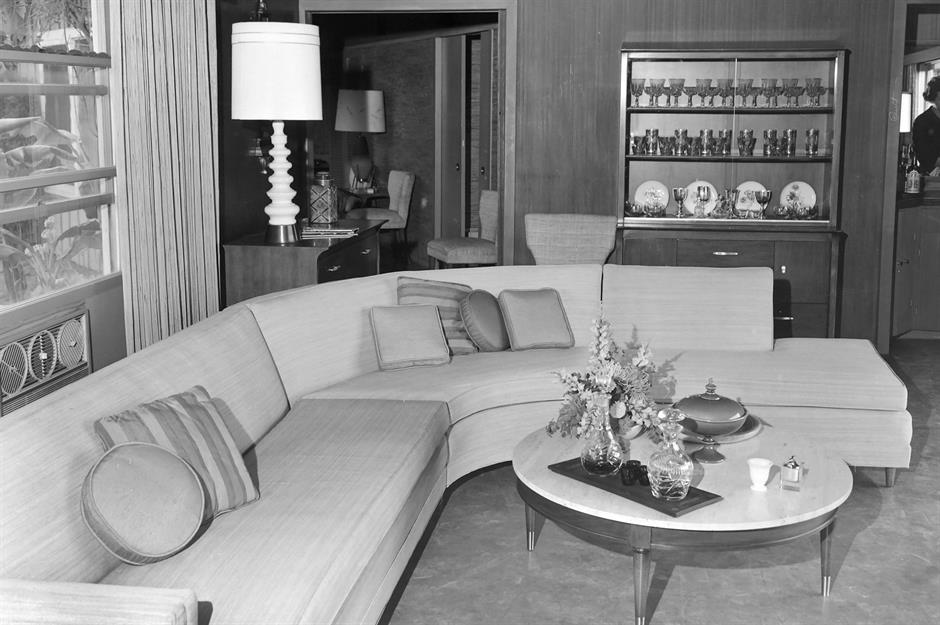

Living rooms in the 1940s

The heart of the home, the living room was where families gathered to listen to the radio, anxiously following the world’s news. Most living rooms also featured phonographs, later better known as gramophones, which played the latest hits from Bing Crosby and Glenn Miller when spirits needed lifting.

In terms of interior design, the 1940s were an eclectic mix of leftover Art Deco glamour and the dawn of mid-century modern minimalism. With furniture – like most goods in short supply, most families kept their furniture from the 1930s throughout the war.

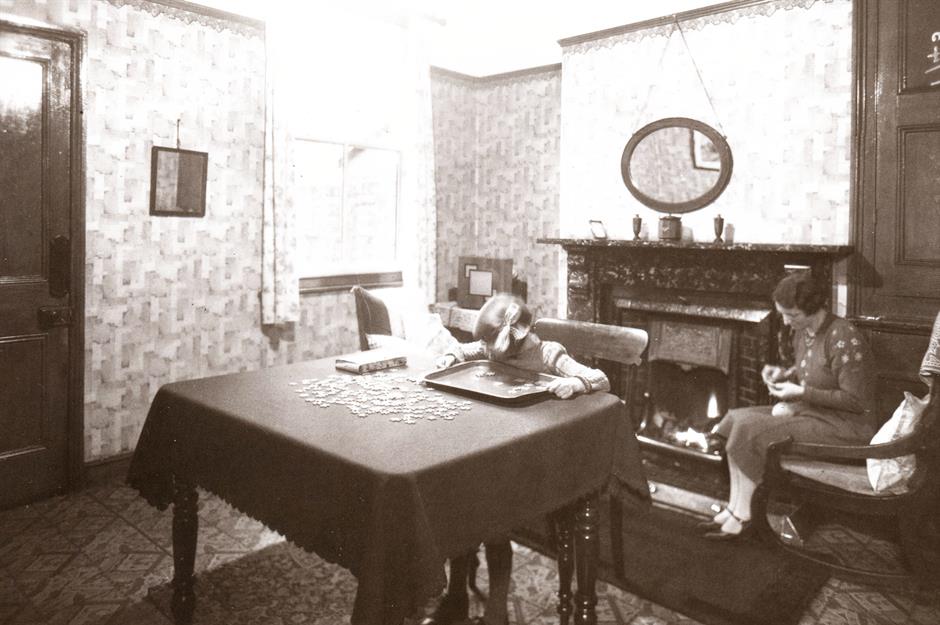

A practical space

In Britain, there would have been thick blackout curtains or boards at the windows. Designed to block out the ambient light, they made it more difficult for cities to be targeted by Germany's Luftwaffe air force bombers and were made mandatory for all households in 1939.

Fuel, too, was in short supply, so fireplaces played an essential part in the home and were another reason the living room became a central gathering place. The living room pictured here is a classic example of a traditionally furnished early 1940s home, with seating gathered close to the warmth of the hearth.

Dining rooms and parlours

Dining rooms underwent a similar stylistic shift over the decade. The traditional setup for a wartime dining room was a table and chairs, a buffet (a cupboard with plenty of storage inside), a china cabinet and a telephone nook (in wealthier homes).

There would often be a timepiece of some sort, perhaps a mantel or grandfather clock, and a fireplace for heat and warmth. If the household had a telephone, it was traditionally kept in this room to prevent calls from interrupting important radio broadcasts in the living room.

Dining room décor

This picture shows a dining room in Yorkshire, England, around 1940. Popular decorations included mirrors, bouquets of wax flowers and chandeliers, even in middle-class homes.

Wallpaper was a popular choice when it came to decorating and there would have been a stash of candles and matches kept close to hand in case of power cuts.

Safety features

In Britain, people who lived in homes without a basement or a bomb shelter would hide underneath their dining room table when the air raid siren rang, and some even swapped their traditional piece for a 'Morrison shelter'.

These came in self-assembly kits that could be configured as a table and aimed to protect the family from falling rubble should their home be hit.

Multi-use Morrison shelters

These multi-purpose pieces of furniture could even double up as a sleeping place for two, allowing residents to rest while sheltering from air raids during the Blitz (as seen here in a home in England in August 1941).

By the end of 1941, half a million Morrison shelters had been distributed. They were strong and extremely valuable to homes without a garden bomb shelter. Plus they didn't have the issue of damp or cold during the winter months.

Bedrooms in the 1940s

More comfortable than a converted table, most 1940s bedrooms featured either double or twin beds with a down-filled duvet, though hot water bottles were often required in colder months due to fuel rationing.

While wardrobes were becoming standard features in new homes, many older homes still used chifforobes – a piece of furniture that combines a wardrobe and a chest of drawers – or dressers instead.

'Make do and mend'

However, wartime rationing of clothes and fabrics meant that people had fewer garments to store than in previous decades, and furniture, too, was in short supply.

Pictured here is a display from the Utility Furniture Exhibition in London in 1942, part of the government-mandated effort to reduce the production of non-war-related items and promote a mentality of 'make do and mend'.

Glamorous boudoirs

This picture shows a substantially more glamorous bedroom from the period belonging to British screen actress Florence Desmond, complete with a mirrored niche and sumptuous oversized satin headboard.

Floral and chintz fabrics were popular for bedding and drapes and large mirrors were standard for both practical and ornamental purposes.

Bathrooms in the 1940s

Luxurious tiled bathrooms were not yet the norm in many low-wage homes in the 1940s. In the UK, many houses still had outdoor lavatories and washing might take place in a bedroom with a wash bowl or in a tin bath in the kitchen. During the war, soap and shampoo were rationed, forcing families to reduce the number of baths they took in a week.

Families were advised to limit the amount of water in their baths to a mere five inches to save on fuel, according to The Imperial War Museum's website. British families were also advised to keep a first aid box in the bathroom to treat minor injuries during air raid attacks.

Anderson shelters

Pre-existing homes also saw wartime updates, largely relating to health and safety. This photo taken in the 1960s depicts a British home that still sports its Anderson shelter. These were an additional structure many Brits constructed in their gardens to provide rudimentary protection during air raids.

Roughly 1.5 million of these shelters had been installed in homes by the outbreak of the war in 1939, according to the RAF Museum, with a further 2.1 million built throughout its duration.

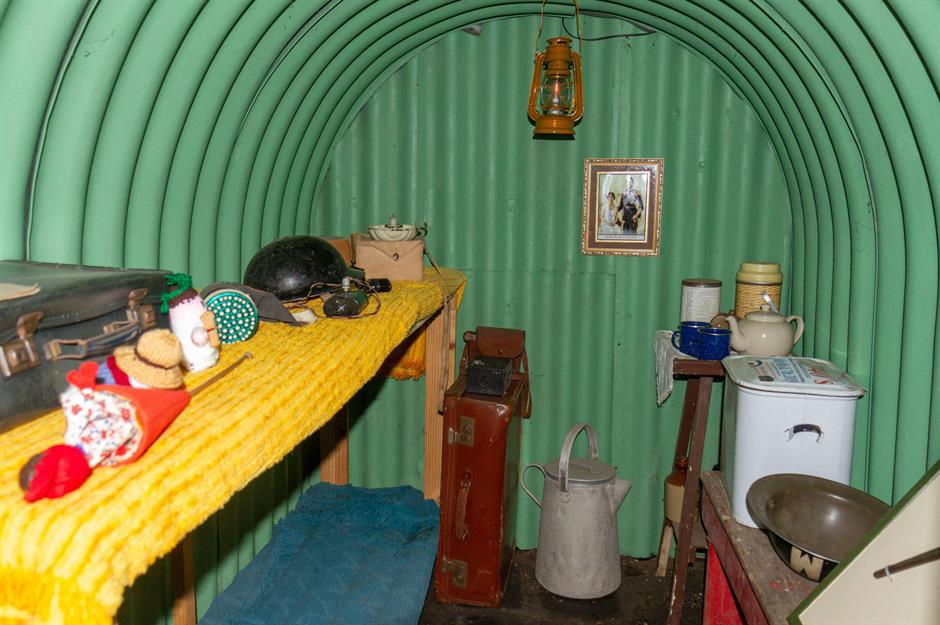

Inside an Anderson

This replica Anderson shelter is at Thorpe Camp Visitor Centre, a WWII Royal Air Force barracks in Lincolnshire, UK. Designed to hold up to six people, they were typically made of sheets of corrugated steel coated in zinc, which provided very effective protection against rusting and made them strong.

Buried as deep as possible underground they were sparsely decorated, with benches for seating (or sleeping if the raid was overnight). Sturdy boxes to store a book or game were common, as well as rations to keep everyone fed.

Victory gardens

Victory gardens were another popular addition to British homes during the war, a trend carried over from the First World War. With widespread food rationing, home production of fresh fruit and vegetables became essential.

Where possible, they were planted in public spaces, too, like this one in London with St Paul's Cathedral seen in the distance. Slogans such as 'digging for victory' and 'our food is fighting' were propagated far and wide and victory gardens were also planted on the grounds of Buckingham Palace and Windsor Castle to inspire the nation to 'get growing'.

Growing their own

These gardens were easily planted in rural and suburban areas and were sometimes even planted on top of Anderson shelters, like the one pictured here. In cities, gardens were squeezed onto rooftops, window boxes or small urban allotments.

The publicity campaigns were a great success and by the end of the war in 1945, Brits were able to produce 75% of their food on home soil, according to The British Nutrition Foundation.

Rural living

During the first few years of the conflict, there was a sense that the war was a far-removed concept with little implication for non-city dwellers, according to the BBC. In reality, rationing had a lower impact on those in rural areas, as many people had farms or allotments as food sources.

But life was far from normal for people living in rural areas of Britain, as around 3.5 million children and vulnerable people were evacuated from cities like London to escape air raids.

Some evacuees found countryside life a little dull and longed for the families they'd left behind. Others enjoyed the fresh air and open spaces and were put to work on farms, which were now crucial for food production.

Farmhouses and country homes

An average farmhouse in the 1940s was typically modest and functional, reflecting a rural lifestyle focused on practicality. The structure was often built from stone, brick or wood, depending on the region, and interiors prioritised utility over luxury. The main rooms usually included a kitchen, a living room, a scullery or pantry and a few small bedrooms. Larger farmhouses might also have a dining room or a separate parlour for taking meals.

The décor was simple, with practical, hard-wearing furnishings. Wallpaper or painted walls in muted colours were common, with floral or geometric patterns and lots of handmade and homespun fabrics used for soft furnishings.

Luxury homes in the 1940s

During the 1940s, the lifestyles of wealthy homeowners in the UK underwent significant transformations due to the Second World War. Affluent families often contributed their estates to the war effort, with grand country houses being converted into facilities such as hospitals, schools and depots.

The war also led to increased taxes and economic controls targeting the wealthy, with estate and income taxes reaching high levels. Well-off individuals were also subject to rationing, with even the royal family – pictured here adhering to clothing coupons. Fearing invasion, some prominent British families even evacuated their children to the US and Canada.

The Blitz

Of course, no discussion of the war would be complete without acknowledgement of the Blitz, the German bombing campaign waged against Great Britain between 1940 and 1941. With its systematic targeting of London, the German Luftwaffe were responsible for the destruction of 3.5 million homes and 9 million square feet (836,127sqm) of office space, rendering 1.5 million people homeless.

With more than 70,000 buildings demolished and another 1.7 million severely damaged as recorded in magazine National Geographic, the city would take decades to fully recover from the assault.

Ready for anything

Of course, the most substantial adjustments to homes were practical rather than aesthetic, designed to conserve resources and protect inhabitants. This was particularly true in the UK, where bombing was an ever-present threat, especially in urban areas.

In addition to Anderson and Morrison shelters, many homes featured Xs taped across pains of glass to try to reduce flying shards in the event of an explosion. Government-issued gas masks also became a regular feature.

The Belfast Blitz

Salvage workers sift through the wreckage of homes in Belfast, Northern Ireland, after a German air raid on April 15, 1941, which killed around 500 people.

The Belfast Blitz saw the Luftwaffe bomb strategic targets, but working-class neighbourhoods bore the brunt of the destruction. Over four nights in April, more than 1,000 residents were killed as incendiary bombs and parachute mines devastated North and East Belfast. Poorly built housing offered little protection, leaving many dead or unidentified.

Northern Ireland contributed to the war effort with 140 warships built in Belfast's Harland and Wolff shipyard and 1,200 Stirling bomber planes manufactured by the city's Short Brothers.

Scotland at war

Valuable for its shipyards, factories and coal mines, Scotland was a major target during the Second World War. As Luftwaffe planes bombed Edinburgh, Glasgow and Aberdeen, Scotland’s east coast provided an attractive potential target for German-occupied Norway.

Though comparatively removed from the centre of the conflict, Scots anxiously awaited news of the war effort and any burgeoning invasion through the radio, like this family pictured here listening to the 1942 Christmas broadcast.

Hosting the Americans

The arrival of US troops in Northern Ireland during World War II brought both disruption and opportunity. In February 1942, the first 6,000 American soldiers landed in Belfast, the first step in a 'friendly invasion' that would see around 300,000 stationed across Northern Ireland by 1945.

Sent in preparation for the European invasion, the troops were eager to join the fight against Hitler. Their presence had a huge impact on local life, with communities organising entertainment for them. To help adjust, soldiers were issued a Pocket Guide to Northern Ireland, warning them about the cold, damp climate and its 200 days of rain per year.

War in Wales

Wales, too, found itself struggling economically while simultaneously being targeted by the German Airforce. Not dissimilar to Ireland, many rural Welsh homes were without water and electricity, forcing families like this one to live very simply.

The family pictured here is taking part in the filming of the documentary, The Silent Village, a propaganda film aiming to illustrate just what might have happened if the Nazis had invaded Wales.

The end of World War II

The Second World War ended in 1945 with Germany's surrender on 7 May, followed by the official acceptance on 8 May, known as VE Day (Victory in Europe Day). Massive celebrations erupted across the UK, France and Europe, with parades, street parties and joyous crowds.

In the Pacific, the war continued until Japan surrendered on 15 August, after the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, marking VJ Day (Victory over Japan). The formal surrender was signed on 2 September 1945. The end of the war brought widespread relief, celebrations and hope for lasting peace across the war-torn world.

Urban migration

The war had generated a massive spike in urbanisation in Britain. Increased production to meet the material needs of the conflict resulted in a vast number of factory jobs, which attracted many migrants and saw people moving from the countryside to the city.

After the end of the war, from 1945 to 1950, some cities experienced another dramatic shift as wealthy families moved out of the centres into the newly created suburbs.

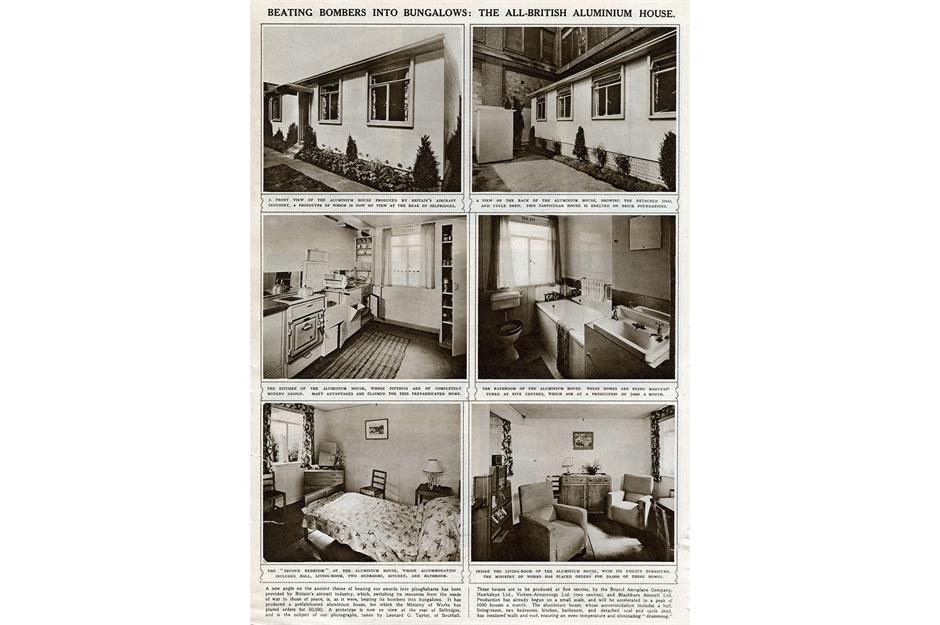

The dawn of prefab architecture

The subsequent housing crisis brought about the dawn of prefab architecture, born of the Housing (Temporary Accommodation) Act 1944.

In his 12-year plan, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill outlined the UK's housing future after the war was won, which required the Ministry of Works to produce Emergency Factory Made Houses, or EFMs. These later came to be known more commonly as prefabs – prefabricated homes.

Cheap and speedy

Prefab models were single-storey detached bungalows consisting of two bedrooms, a living room, a fully equipped kitchen and a bathroom, as this advertisement from 1945 illustrates.

They were designed to be cheap to produce, quick to assemble and, while far from ideal, were a significant improvement on previous emergency housing, which included encampments in Epping Forest and bunk beds set up underground in tube stations.

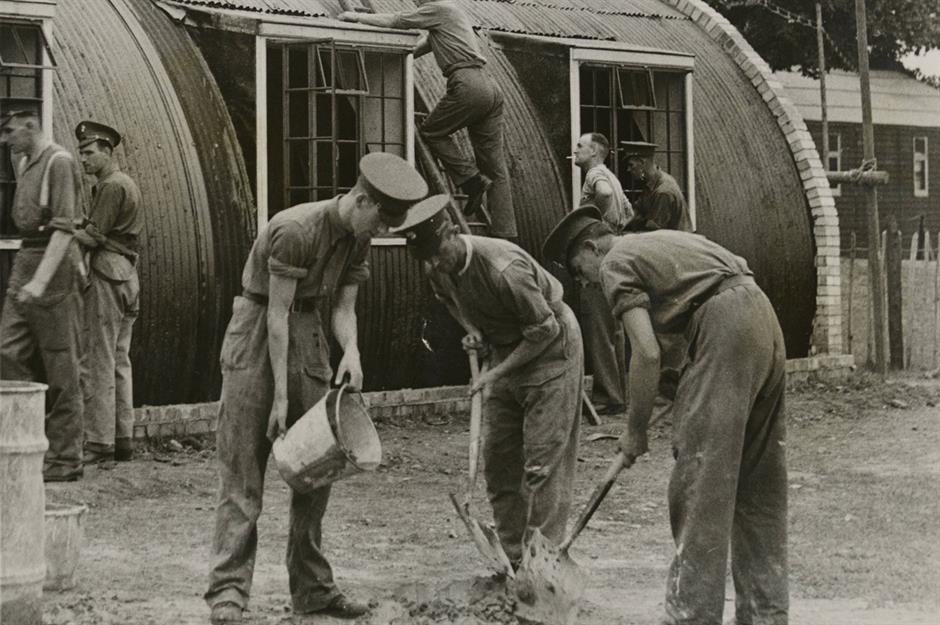

Repurposing the army

To get these homes built as efficiently as possible, Britain harnessed the power of its victorious military with the Army Vocational Training Centre. This programme trained former army officers to build these new prefab homes.

Pictured here, Grenadier Guards work to erect a Nissen hut in Windsor.

Out with the old, in with the new

Meanwhile, for those not facing a housing crisis, the end of the war brought about dramatic changes in interior design. As rations were gradually lifted and economies shuddered back into life, the UK saw a rise in consumer culture.

Homes became more functional and less formal, with an emphasis on material goods which could now be mass-produced thanks to new processes developed during the war.

Moving towards mid-century modernism

Once wartime restrictions were lifted and families were free to spend again, many living rooms got a mid-century minimalist facelift.

Mid-century furnishings featured sleek, streamlined silhouettes, glass tables, geometric prints and orange, brown and green colour palettes. Man-made materials such as plastic and fibreglass came into prominence, as did warm woods such as teak and rosewood.

The dawn of a new decade

As the 1940s gave way to the 1950s, the UK entered a new era of rebuilding, reimagining and reinventing what the modern home should look like; a new style of home for a new style of living.

Several distinctive architectural styles emerged inspired by the optimism and technological leaps of this transformative decade. People's homes, buildings and lives would never be the same again...

Loved this? Now discover more spectacular historic homes

Comments

Be the first to comment

Do you want to comment on this article? You need to be signed in for this feature