American icon: the Chrysler Building's incredible secrets

A jewel of New York

A city on the up

At the turn of the 20th century, New York City was an emerging metropolis and busy seaport. In the years of rapid industrialisation leading up to the 1920s, individuals amassed huge personal fortunes like never before. Industry was booming, Wall Street was reaching new plateaus of prosperity and New York was the centre of it all. America’s corporations and new super-rich scrambled to buy up real estate in Manhattan and erect their own towering monoliths.

The origin story

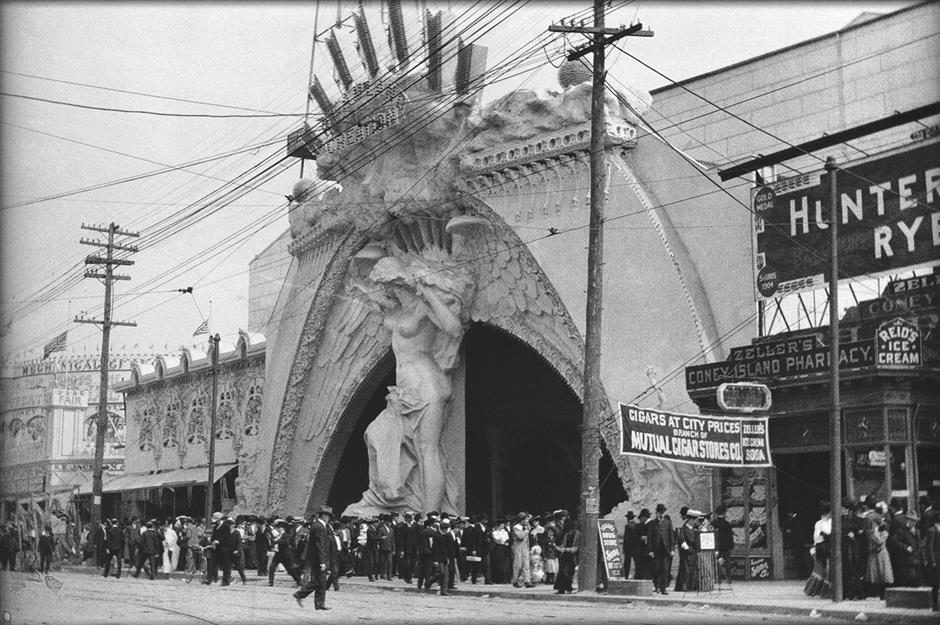

He may not have his name above the door, but the building’s beginnings actually started with developer and Senator William H Reynolds. After his Coney Island pleasure park Dreamland (pictured) burned down in 1911, he set his sights on Manhattan and bought a prime piece of real estate on the corner of 42nd Street and Lexington Avenue, a stone’s throw away from Grand Central Station. He even hired architecture’s rising star William Van Alen to come up with a plan for an unusual skyscraper…

A private ambition

Car magnate Walter P Chrysler was looking for an extraordinary New York home for the Chrysler Corp., his personal business venture that he founded and owned. This was to be paid out of his own fortune and as such should be a monument to the man and his family name. In 1928, after Van Alen’s ever-increasing ambitions finally broke the budget, Reynolds sold the lease on the plot, the architect’s services and the design for an 808-foot tower to Chrysler, for a measly $2 million – around $29 million (£23.5m) in today’s money.

The first ‘star-chitects’

In five heady years between 1928 and 1933, construction work was completed on the New York Life Building (615ft), 30 Rockefeller Plaza (850ft), 40 Wall Street (927ft) and the Chrysler Building (1,046ft). Architects became household names in their own right and synonymous with their creations. Here, Van Alen (fourth from left), stands tallest dressed as the Chrysler Building, among his fellow architects and their own buildings for the Beaux Arts Ball in 1931.

William Van Alen: a modernist

William Van Alen was one of the new breed of architects ready to blow away the cobwebs of building conventions in favour of a new streamlined approach. Van Alen explained his philosophy: “In designing a skyscraper there is no precedent to follow for the reason that we are using a new structural material, steel, which has been developed in America and is different in every way from the masonry construction of the past.” (Neal Bascomb, Higher)

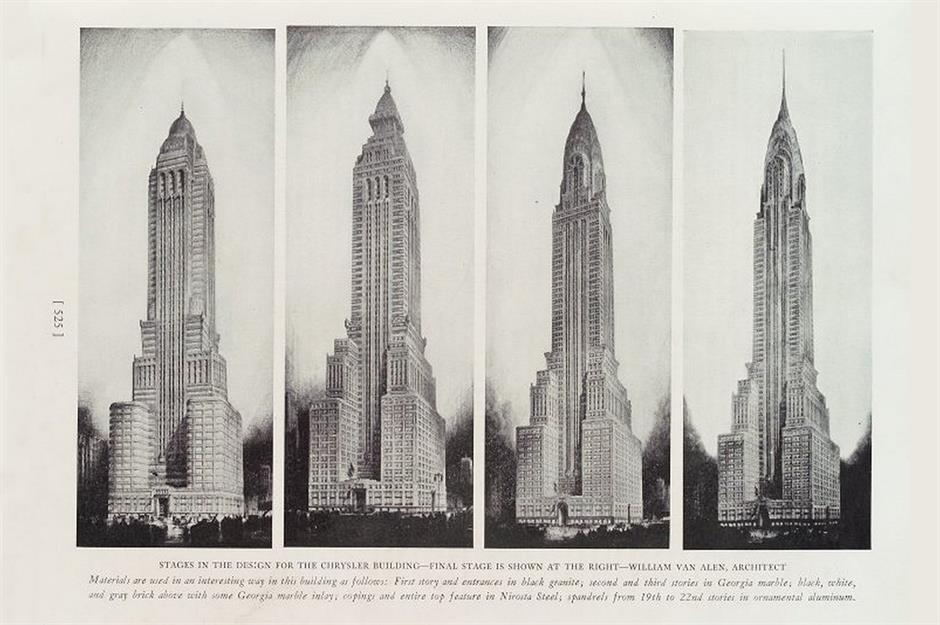

First drafts

A series of drawings by Van Alen shows alternate designs for the building’s crown, ranging from a rounded dome with a short spike to a four-sided finial. The caption reads: “Materials are used in an interesting way in this building as follows: First storey and entrances in black granite; second and third stories in Georgia Marble, black, white and grey brick along with some Georgia marble inlay; copings and entire top feature in Nirosta Steel; spandrels from 19th to 22nd stories in ornamental aluminium.”

Chrysler’s eye for detail

If Van Alen’s vision had been too much for Reynolds, in Chrysler he found a client whose ambitions outstripped even his own. As an engineer, Chrysler’s eye for detail was legendary and he requested hundreds of revisions to the architect’s first designs. Money was no object for the multimillionaire (a billionaire in today’s dollars), and he was willing to spend whatever it took to realise their shared dream. However, the pair never formally agreed on a fee, an oversight that would come back to haunt them…

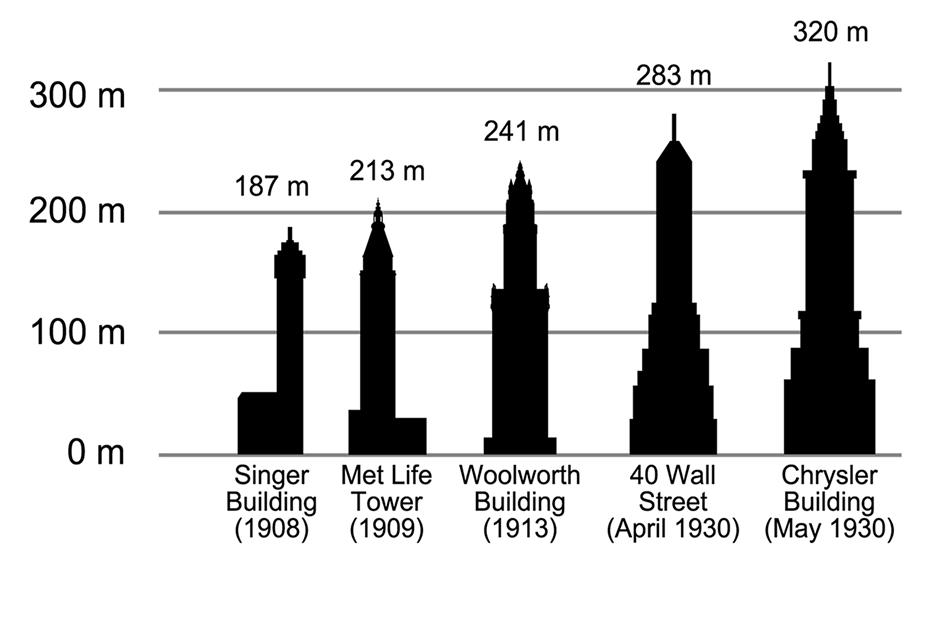

Race with his rival

The build was also a bitter battle between Van Alen and his former architecture partner, H Craig Severance, who was simultaneously working on the new skyscraper HQ for the Bank of Manhattan at 40 Wall Street – now better known as the Trump Building. The rivalry led to them altering their plans mid-construction as each tried to outdo the other, pushing Van Alen to make his creation ever taller, shaping the iconic needle out of a desire for victory over his arch-nemesis.

A homage to Chrysler

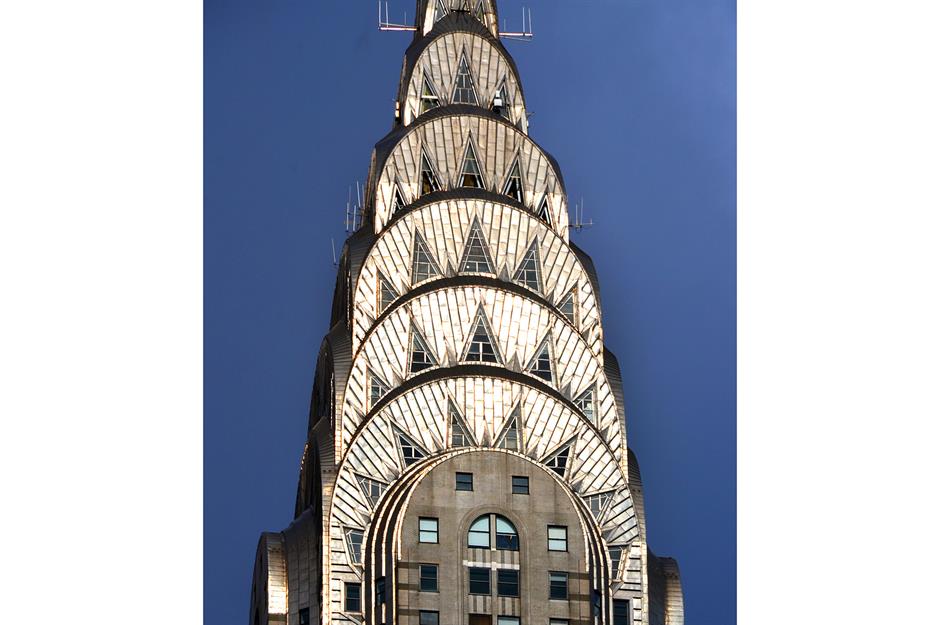

Finally, a design was agreed. Starting at the base with its monochrome brick exterior, the tower tapers as it rises over 77 floors, with the 31st and 61st floors marked by huge stylised chrome gargoyles and eagles that were fabricated in sheet metal workshops inside the building. Finally, the Art Deco flourish at its peak; scalloped curves of glinting metal beneath the needle-sharp spire, making it look like the diamond pendant on the neck of the New York skyline.

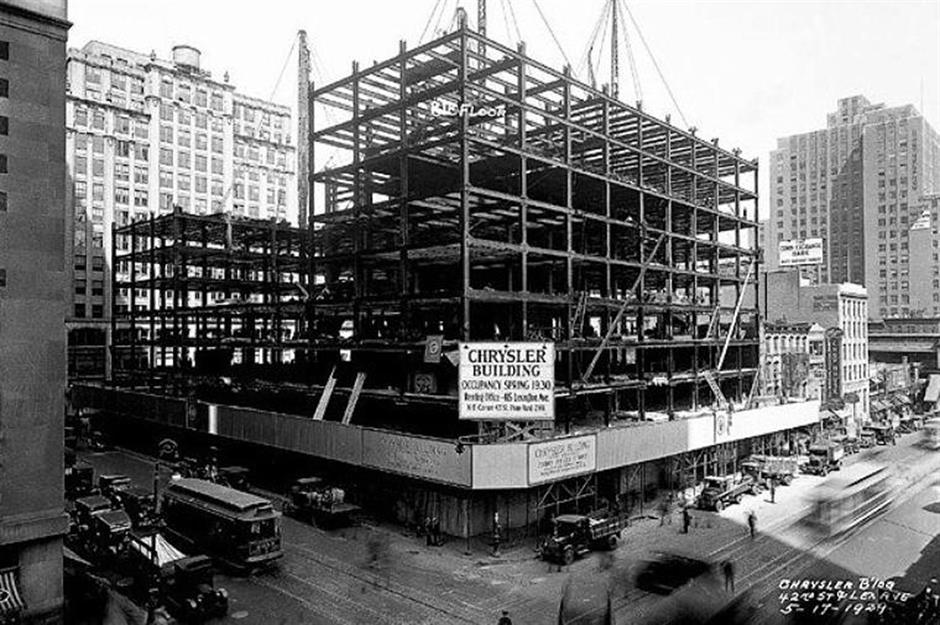

The build begins

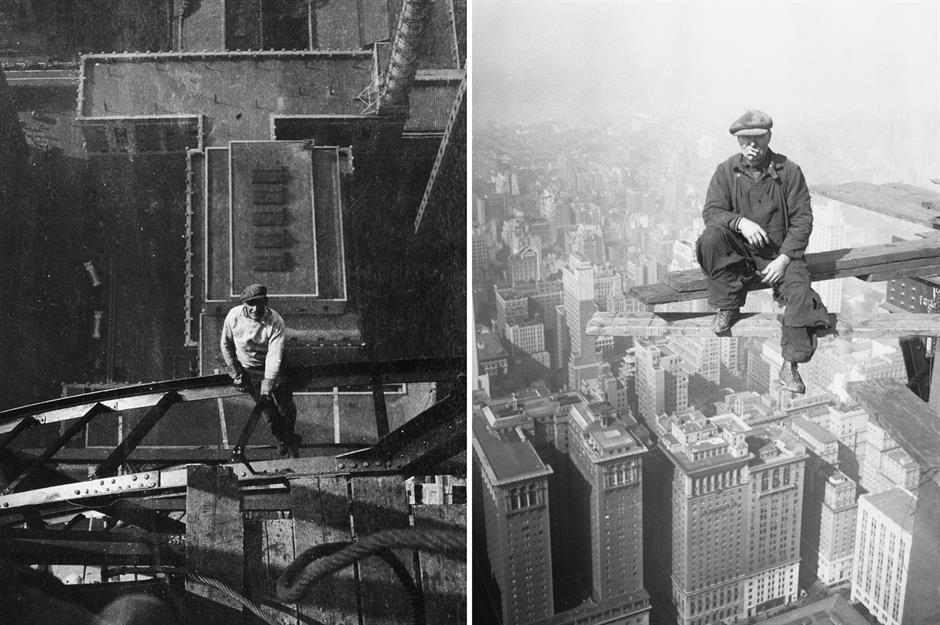

Incredible workforce

None of New York’s golden age skyscrapers would have seen the light of day without a huge number of highly skilled workers, flooding into the city from all over the world. Organised by trade into gangs of riveters, scaffolders, bricklayers and more, these 3,000 fearless men were working at nosebleed heights without harnesses or helmets. In total, nearly 400,000 searing hot rivets were heated up, thrown with metal tongs and caught with special metal cones before being hammered into position, while approximately 3.8 million bricks were laid by hand.

The exterior elements

With its Gothic eaves, hubcap friezes and stainless steel gargoyles shaped like the hood ornaments of a 1929 Chrysler, the building pays tribute to the engineering and sleek design of its automobile namesake. Van Alen was able to merge decorative elements with integral structural aspects so that the building was at once practical and beautiful.

The sunburst

Echoing the diadem of the Statue of Liberty, the triangular sunbursts are made from silver nickel steel (a special metal called Nirosta designed by the German company Krupp). They are designed to never rust and sparkle when they catch the sun.

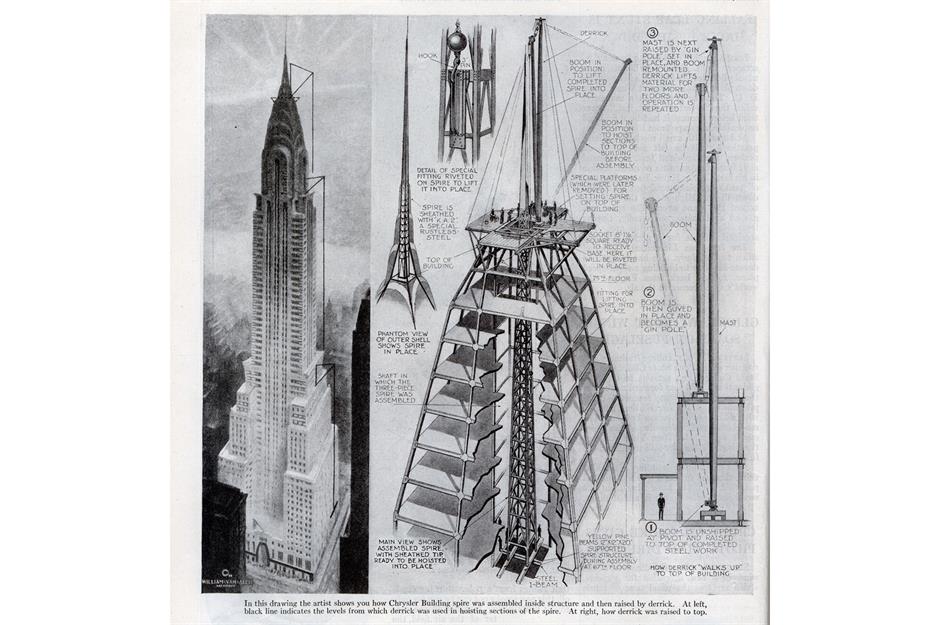

The secret weapon

In the race for the sky, Van Alen had an ace card up his sleeve. A monel spike (an early form of stainless steel) was built in secret within the building's tower and at the last minute pushed up to crown the top and make it taller than his rival's. On October 16th 1929, the 185-foot-high spike emerged from the top and was bolted into place, raising the building’s overall height to 1,048 feet, 121 feet taller than its rival.

The spire

The following year, Van Alen wrote in Architectural Forum magazine (reported in the New York Post): “The signal was given and the spire gradually emerged from the top of the dome like a butterfly from its cocoon, and in about 90 minutes was securely riveted in position, the highest piece of stationary steel in the world.”

The grand opening

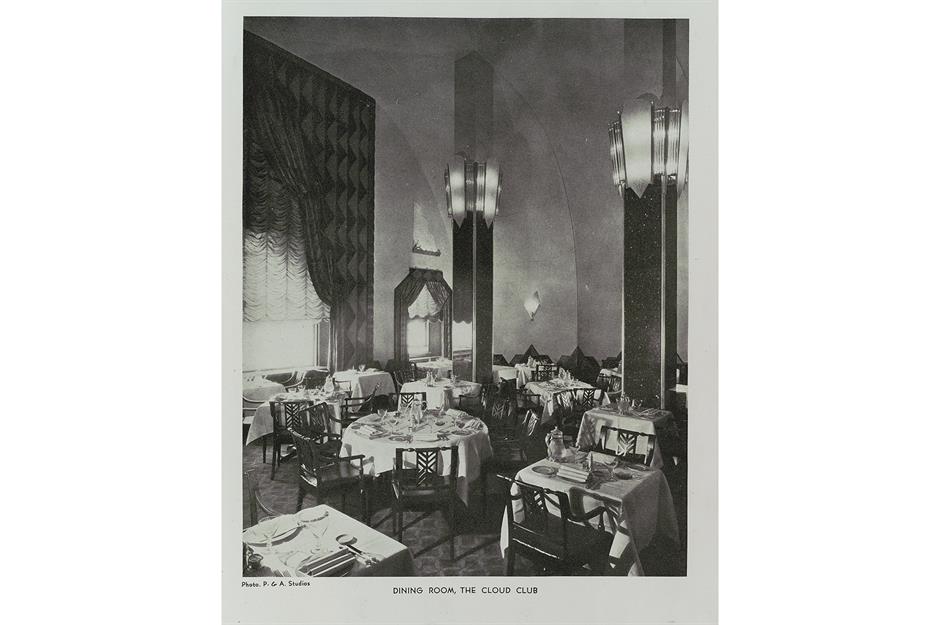

The Cloud Club

The interior

A dream realised

Taller than the Eiffel Tower (until a new antenna was added in 1957), taller than the Woolworth Building and taller than his old rival's Bank of Manhattan Building, Van Alen had succeeded in putting Chrysler's name into the clouds. But the absence of a contract came back to haunt them both. Van Alen asked for 6% of the budget fee, which Chrysler refused to pay him and the pair ended up in court. Van Alen won the case, but his reputation for being litigious ruined his career in architecture and he eventually became a sculpture teacher.

Over the years

Chrysler died just 10 years after the building was completed and it passed to his family, and then on to developers in the 1960s. Through the decades, the Chrysler Building has been used as corporate office space, although there were also a few apartments within the building: Walter had the penthouse, of course, and Life magazine photographer Margaret Bourke-White had one on the same floor as the gargoyles she famously risked her life to photograph. During the 1970s, when crime rates and economic hardship nearly bankrupted New York City, the future of the building looked uncertain and the interior started to fall into disrepair.

A piece of history for sale

After years of passing through different hands, real estate investors Tishman Speyer stepped in and bought the Chrysler Building for $220 million (£178m) in 1997. They spent $100 million (£81m) refurbishing the tower before selling on a 90% stake to the Abu Dhabi Investment Council (ADIC) in 2008 for $800 million (£649m). Then in 2019, it was put up for sale again and bought for a mere $150 million (£122m) by property management firm RFR and Signa Holding, a European investment company.

An American icon

While the future is unknown for the interior of the building, as a legally protected landmark, New Yorkers can rest assured that this legendary tower will be around for years to come. Long may she reign!

Loved this? Find out the incredible secrets of these 13 abandoned stately homes

Comments

Be the first to comment

Do you want to comment on this article? You need to be signed in for this feature